This was written as the introduction for the Mesilla Valley Film Society’s screening of Pickup on South Street in November, 2024.

Samuel Fuller’s Pickup on South Street stands as one of the most visceral and authentic crime films of the 1950s, its gritty realism stemming directly from Fuller’s own experiences as a teenage crime reporter. At just 17, Fuller worked the streets of New York for the Evening Graphic, soaking up the raw material that would later inform his filmmaking. This firsthand knowledge of the criminal underworld permeates every frame of the film, from the accurate portrayal of pickpocket techniques to the street-level authenticity of its dialogue, where terms like “cannon” (the real insider slang for pickpockets) pepper the characters’ exchanges.

Fuller’s path to 20th Century Fox was as unconventional as his filmmaking style. His early independent productions, particularly The Steel Helmet (1951) and Park Row (1952), caught the attention of studio head Darryl F. Zanuck, who recognized in Fuller a unique and uncompromising voice. Their resulting arrangement was remarkably unusual for the studio system: Fuller would be contracted to Fox for only six months of each year, leaving him free to pursue independent productions during the remaining months.

This hybrid approach allowed Fuller to maintain his creative independence while accessing studio resources, a balance that would prove crucial for films like Pickup on South Street. It also allowed him to keep his budget-friendly filmmaking ethos, even when on the Fox lot.

“Sometimes you look for oil, you hit a gusher.”

This is a movie that really does showcase Fuller’s sharp instincts as a storyteller. When Zanuck presented him with Dwight Taylor’s script Blaze of Glory—a courtroom drama about a female lawyer falling for her criminal client — Fuller saw the potential for something more immediate and kinetic. After all, he knew how long court cases could take and how difficult it was to make one genuinely exciting without resulting to the kind of narrative tricks he disdained.

In Fuller’s story, Skip McCoy, a skilled pickpocket fresh off his third conviction, unknowingly lifts a piece of microfilm bound for communist agents from the purse of Candy. She’s a tough-talking woman who believes she’s merely carrying “business papers” for her ex-boyfriend Joey.

When both the FBI and Joey’s communist handlers begin pursuing Skip for the film, Candy finds herself caught between her growing attraction to Skip and pressure to retrieve the microfilm. Meanwhile, Moe, an aging street peddler who sells ties and information with equal shrewdness, becomes entangled in the increasingly dangerous situation.

As the stakes escalate, what begins as a simple pickpocketing evolves into a complex web of loyalty, patriotism, and unexpected romance, culminating in one of the best examples of the genre.

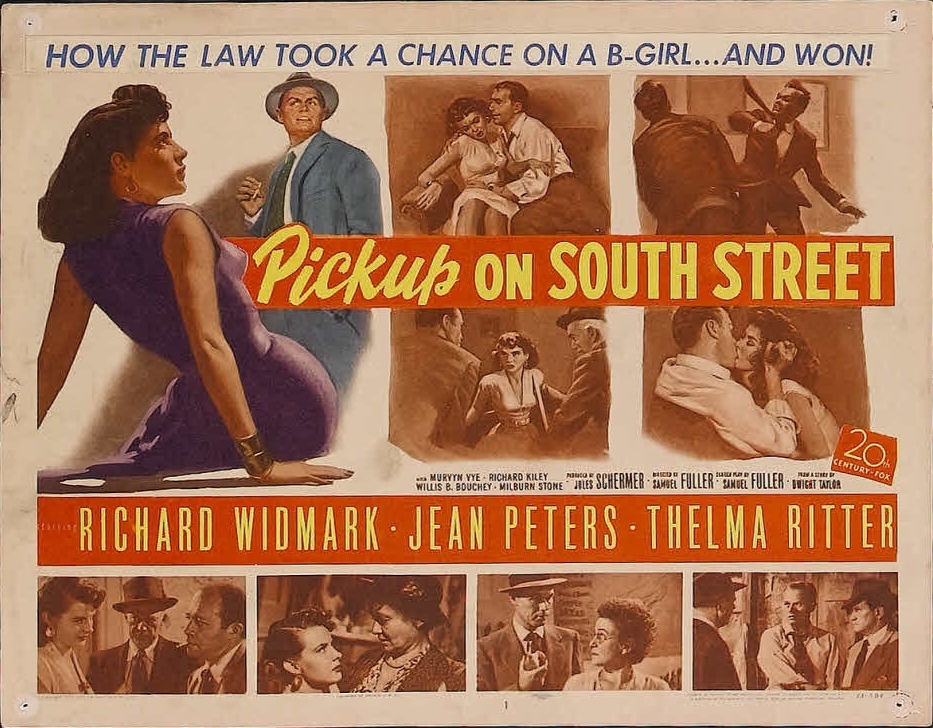

The film’s casting is as masterful as its plot. Richard Widmark, already established as a noir powerhouse through his unforgettable performances as the maniacal Udo in Kiss of Death (1947) and the desperate conman Harry Fabian Night and the City (1950), took on the role of Skip McCoy. Widmark’s portrayal of the three-time convicted pickpocket manages to be inexplicably charismatic despite the character’s unrepentant nature. His natural ability to imbue morally compromised characters with magnetic charm made Skip McCoy one of noir’s most compelling antiheroes. (Unfortunately, Widmark’s next collaboration with Fuller in 1954’s submarine thriller Hell and High Water, would prove far less successful, lacking the electric energy of their first pairing.)

The role of Candy produced its own behind-the-scenes drama. Marilyn Monroe, then rising rapidly through Hollywood’s ranks, actually sat in on rehearsals and read for the part. Fuller, while impressed with Monroe, made the bold decision to reject her, diplomatically citing her “overwhelming sensuality” as wrong for the character. Even more surprisingly, Betty Grable, one of 20th Century Fox’s biggest stars, lobbied for the role, initially demanding the inclusion of a dance number. When Fuller refused, Grable offered to do the film without the dance, but by then, the director had found his Candy in Jean Peters. Fuller’s instincts, proved correct, just as they usually did; Peters brought exactly the right mix of toughness and vulnerability to the role.

Perhaps the film’s most memorable performance comes from Thelma Ritter as the street-wise informant Moe Williams. Her portrayal earned her a fourth consecutive Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress, following nods for All About Eve (1950), The Mating Season (1951), and With a Song in My Heart (1952). Despite the strength of her performance, she would lose to Donna Reed for From Here to Eternity. Ritter would earn two more nominations in her career but, remarkably, never won the award.

Technically, the film showcases Fuller’s sophisticated yet understated approach to direction. A standout example is the luxuriously long take that introduces Moe in the police office. The scene feels remarkably modern, even Spielberg-esque, in its invisible technique that prioritizes character development over technical showmanship.

For a man who reported hated violence, Fuller was a master at using it on-screen, much like Sam Peckinpah. His unflinching approach is particularly evident in the still-shocking confrontation between Joey and Candy, a scene that maintains its power to disturb today’s audiences.

The current restoration of the film (available through Criterion on a well-appointed disc) highlights these artistic choices, with pristine black levels and shadow detail that enhance the noir in film noir.

“Even in our crummy line of business you gotta draw the line somewhere.”

The film’s political context proved as explosive as its on-screen action. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was so disturbed by the film’s portrayal of an unpatriotic protagonist—particularly Skip’s initial indifference to the communist threat—that he demanded a meeting with both Zanuck and Fuller. When Hoover pushed for changes to the film, Zanuck stood firmly behind Fuller’s vision, though this principled stance came at a cost. The studio’s previously close relationship with the FBI was severed, and all references to the agency were stripped from the film’s marketing materials.

Despite mixed critical responses — both Variety and my most the Times’ Bosley Crowther ended up kind of shrugging at the whole picture — Pickup on South Street proved a commercial success and helped secure Fuller as an asset at Fox.

Oddly enough, the movie’s apolitical plot (everyone’s in it for the money) proved controversial overseas. After it was deemed to be anti-communist propaganda, it was was released as Le Port de la Drogue (The Drug Port), with the Cold War espionage elements completely rewritten to focus on drug trafficking instead. This curious transformation speaks to the film’s malleable themes of loyalty, survival, and moral ambiguity that transcend specific political contexts.

Fuller’s fusion of hard-boiled crime drama with Cold War paranoia created something unique in American cinema—a film that works both as pure genre entertainment and as a complex exploration of loyalty and patriotism in morally ambiguous times. Pickup on South Street remains a testament to Fuller’s journalistic eye for detail, his unflinching approach to violence, and his ability to find humanity in the most hardened characters. The film stands as one of the most distinctive entries in the noir canon, its influence visible in countless crime films that followed.

Leave a Reply