Fritz Lang is one of those directors whose name is synonymous with film noir: a German expatriate who brought his expressionistic storytelling technique to Hollywood and quickly began to change how studio films looked and felt. His debut, Fury (which I talk about here) still shocks in spite of its studio-mandated happy ending, and movies like The Woman In The Window and Scarlet Street1both starring the excellent Edward G. Robinson showed that you could elevate the basic, budget-friendly thriller with creative photography and direction that allowed the audience to care more about the characters than the plot.

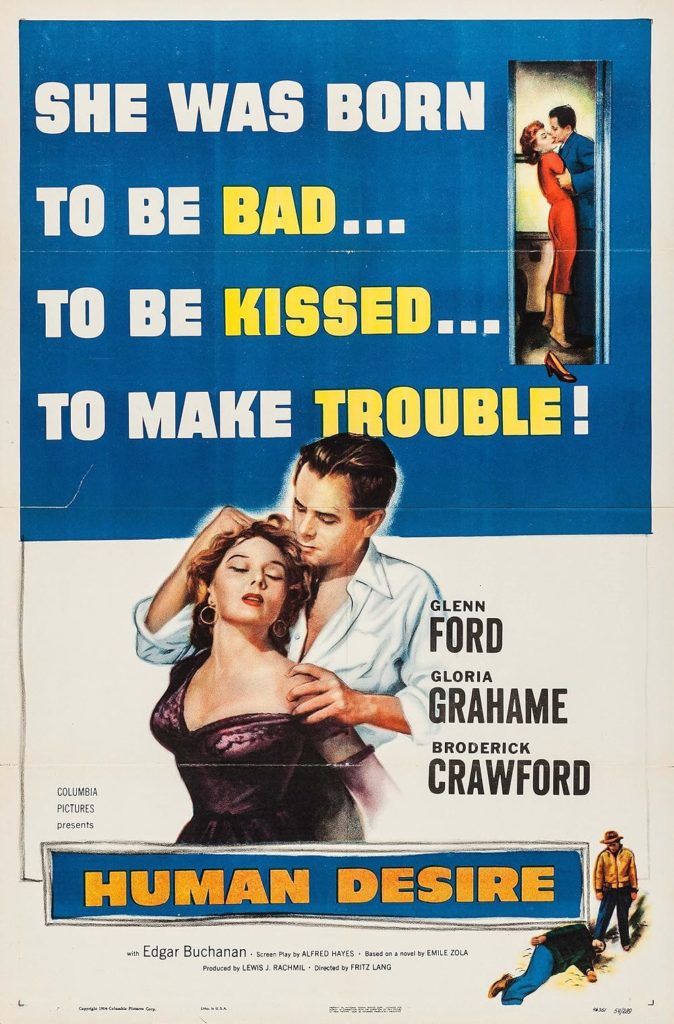

In 1953, he teamed up with Glenn Ford to make one of the genre’s all-timers, The Big Heat, in which a cop single-handedly takes revenge on the criminal syndicate that rules his city. The critics loved it, it made the studio a lot of money, and Ford and Lang would be reunited a year later for Human Desire.

An Unnamed City, A Seemingly-Familiar Story

Loosely based on a book by Émile Zola,2That had been filmed twice before as Renoir’s La Bête Humaine and Die Bestie im Menschen, directed by Ludwig Wolff. Human Desire kicks off with a wholesome, all-American scene: Jeff Warren (Ford), freshly discharged from the Army after service in Korea, returns to his hometown to pick up where he left off, starting with his duties as a train engineer for the Central North Railroad. We get to see that while most things haven’t changed — Jeff’s coworkers are the same guys with the same complaints and his boss barely looks his way — two notable shifts have occurred that will impact him directly.

First of all, he discovers that Ellen, the daughter of his best friend3Played by Edgar Buchanan, who would go on to make a dozen movies and the first season of a TV show with Ford. is now an enchanting young woman. The second, more important change: the alcoholic yard supervisor Carl Buckley (Broderick Crawford) went and got married to the gorgeous young Vicki (Gloria Grahame). Vicki’s got a past, Carl can’t handle it, and things spiral out of control, creating a vortex that drags Jeff down.

Ford’s exceptional as the everyman who’s obviously carrying a bit of the war inside him still. Despite the smiles and warm reunions, Jeff’s a guy that just doesn’t know what to do with himself when he’s not working, and that’s one of the reasons he gets sucked into the deeply murky Vicki/Carl situation. Jeff knows he shouldn’t get involved with Vicki, especially with it being obvious that Ellen is the better choice for him, but noir has never been about making the better choice. Jeff has nothing to call his own; Vicki wants him. It’s just that simple.

Lang’s mastery of the medium is on display, as is to be expected. It may not have the expressionist photography of his earlier films, but Human Desire’s inversions of some key genre tropes, deliberate tonal shifts and pacing, and use of pure visual storytelling4When you watch the movie, check out Carl and Vicki’s home and how they live. He’s given her everything she could want and she’s still not happy. elevates it above the vast majority of the melodramas it was competing against. Even that happy ending that the studio craved ends up being subverted in a way that perfectly matches the rest of the film.

Critics at the time weren’t crazy about this one: Variety complained that Lang went “overboard in his desire to create mood” and the New York Times complained that there wasn’t a reason to care about anyone in the picture. Obviously, I think that’s hogwash if I’ve decided to spend my morning writing about it. It’s currently not streaming anywhere, but Kino Lorber’s new disc is worth picking up.

Leave a Reply