Filmmaker, painter, musician, and actual damn Renaissance Man David Lynch died today at the age of 78 after a brief struggle with emphysema, the result of decades of smoking.

Born in Missoula, Montana in 1946, Lynch grew up in a Norman Rockwell-esque series of small towns, living the idyllic Boomer life that saturated TV in the 50s and 60s. However, he also saw the gloom and secrets that lurked behind closed doors and in dark alleys.1He’s always been cagey about what drove him, but it’s apparent from his autobiography and various interviews that he saw some shit. He took that suburban darkness with him to Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, which he attended from 1966 to 1967.

His time at PAFA was brief but transformative. A watershed moment occured one night when he was staring at his latest piece, a pure black painting, when he saw it move despite the fact that it was literally just a canvas completely covered in paint. Outside, the wind was blowing, and it gave him the idea of combining movement with his art work. Soon after, he debuted his first animation project, “Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times),” which was basically a sculptural film installation with looped animation projected onto a specially prepared screen with built-in sound.2You can learn more about this period in the documentary The Art Life.

After leaving PAFA, he bounced between Philadelphia and Boston, picking up work to support his art, including a short gig at a frame manufacturing company. In 1970, he got accepted into the American Film Institute Conservatory in Los Angeles and with him he brought a 45-page script that would become his first film, Eraserhead.

It would take him five years to finish the movie. He’d get started, funding would dry up, and he’d have to take side gigs (including a paper route) to get things moving again. This took a heavy toll on his personal life; he basically lived in the stables-turned-film-sets where they were shooting the movie while his first marriage was falling apart.

The sounds of the industrial wasteland around the studios, combined with the urban decay fueled the final film, a black and white masterpiece about parenthood and industrial anxiety established Lynch’s signature style: dream logic, oppressive soundscapes, and that uniquely Lynchian ability to make the mundane terrifying.

Eraserhead hit the midnight movie circuit in 1977. It initially baffled critics (early reviews read like people trying to describe a Nyquil dream), but it gradually emerged as a crucial puzzle piece in American avant-garde cinema. The film didn’t just launch Lynch’s career – it basically created its own aesthetic category. That densely layered sound design, those impossibly dark corridors, the way mundane objects become menacing? That DNA exists in the works of David Cronenberg and Darren Aronofsky, to name just two of the creators who were informed by his work.

Producer Mel Brooks (who deliberately kept his name off the credits to avoid people thinking it was a comedy) saw Eraserhead and hired Lynch to direct The Elephant Man (1980), a Victorian-era drama based on the life of Joseph Merrick, often called John Merrick in historical accounts and in the film. The Elephant Man marked Lynch’s transition from experimental filmmaker to someone who could work within the Hollywood system while maintaining his artistic vision.

With (again, stunning) black and white cinematography and an extraordinary performance by John Hurt under complex prosthetic makeup, the film tells Merrick’s story through his relationship with Dr. Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins). Lynch brought a deep humanity to the material, finding a perfect balance between his surrealist instincts and historical drama.

The film was a critical and commercial success, earning eight Academy Award nominations including Best Picture and Best Director. Its exclusion from the Best Makeup category actually led to the creation of that Oscar category the following year. The movie helped establish Lynch as a serious filmmaker who could work with major stars and studios while preserving his unique sensibilities.

Perhaps most importantly, Lynch brought dignity to Merrick’s story, avoiding exploitation while exploring themes of humanity, cruelty, and compassion that would recur throughout his later work.

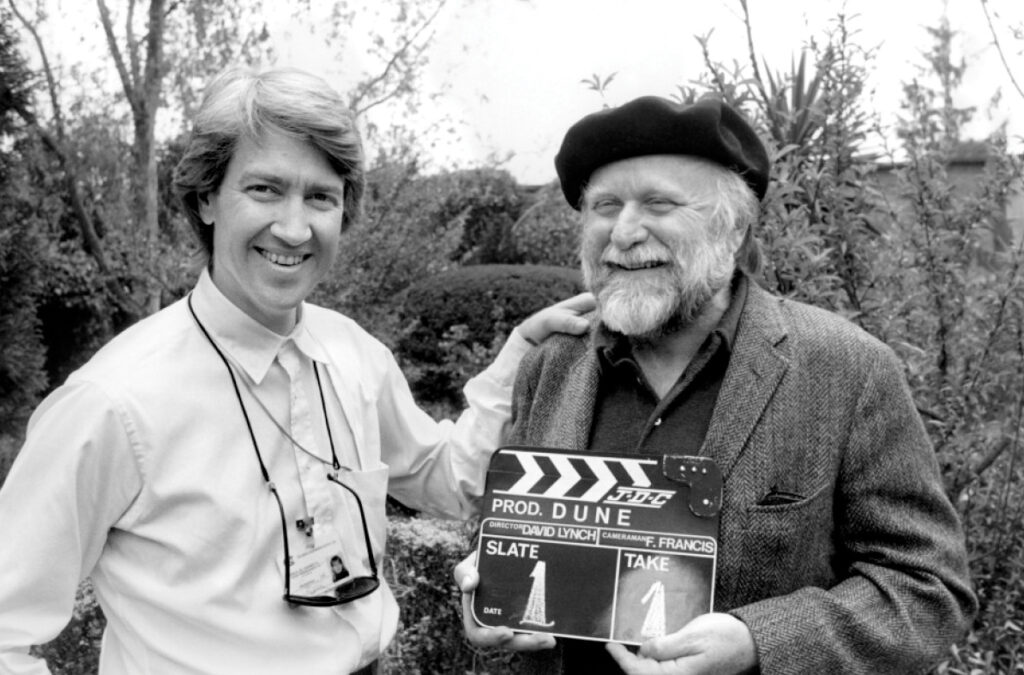

After The Elephant Man’s success, Lynch took on an ambitious adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune (1984), a project that would become one of his most challenging experiences. Infamous producer Dino De Laurentiis gave Lynch a $40 million budget and remarkable creative freedom, but the filmmaker soon found himself trapped in a complex production that strayed far from his comfort zone.

Lynch created some truly memorable visuals for Dune: the massive sandworms, the truly alien Guild Navigators, the grotesque Baron Harkonnen, and the industrial-gothic architecture of the Harkonnens’ home world Giedi Primem to name a few, all backed by a fascinating electronic score by yacht rock icons Toto and Brian Eno. That wasn’t enough, though.

The need to compress Herbert’s dense novel into a theatrical runtime3A mistake Denis Villanueve would not make. resulted in a confusing narrative filled with clunky exposition (including the infamous internal monologues). The studio’s interference and final cut left Lynch so disappointed that he has largely disowned the film. Despite its commercial and critical failure, Dune remains a fascinating entry in Lynch’s filmography, showing what happens when his surrealist sensibilities collide with big-budget science fiction.4It’s also the version of the story I like most. Yes, I said it, and I’ll say it again. You can’t stop me.

Blue Velvet (1986) marked Lynch’s return to personal filmmaking, establishing many of the themes and aesthetic touches that would define his later work. The film begins when Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) discovers a severed human ear in a field, leading him into the dark underbelly of his seemingly idyllic hometown of Lumberton.

The film masterfully weaves between the bright, artificial wholesomeness of small-town, White America (complete with white picket fences and bobby sox) and its shadow world, embodied by Dennis Hopper’s nitrous-huffing gangster Frank Booth and Isabella Rossellini’s troubled lounge singer Dorothy Vallens. Lynch creates an atmosphere where these two worlds exist simultaneously, recreating the imagery he’d had in his head from a young age.

What makes Blue Velvet particularly striking is how it combines Lynch’s experimental sensibilities with noir storytelling conventions. The opening sequence – moving from bright suburban imagery to a closeup of insects writhing beneath a lawn – perfectly encapsulates the film’s exploration of surface and depth. The film’s sound design, mixing Bobby Vinton’s titular song with industrial noise and Angelo Badalamenti’s haunting score, would become a Lynch trademark. Controversial upon release, Blue Velvet is now considered one of the defining films of the 1980s.

After shooting a pilot for TV5More on that in a bit., Lynch would adapt Barry Gifford’s novel Wild at Heart (1990). A hyperkinetic love story about Sailor (Nicolas Cage) and Lula (Laura Dern), two young lovers fleeing Lula’s maniacal mother (a like-you-never-saw-her-before-or-since Diane Ladd). Lynch infuses the film with references to The Wizard of Oz while amplifying the novel’s more lurid threads to a violent, sexually charged road movie through the American South.

The film pulses with raw energy, fueled by uninhibited performances by Cage and Dern. Sailor’s snakeskin jacket and Elvis fixation, Willem Dafoe’s appearance as the grotesque Bobby Peru, and surreal touches like a burning match filling the screen create an atmosphere where love story meets fever dream. While some critics (wrongly) found it excessive, the film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

It’s overlooked by many, but Wild at Heart stands as Lynch’s most direct exploration of romantic love, albeit filtered through his unique sensibility. The film’s heady blend of extreme violence, dark humor, and genuine tenderness makes it one of his most emotionally accessible works.

Oh, and that TV pilot he shot? You may have heard of it.

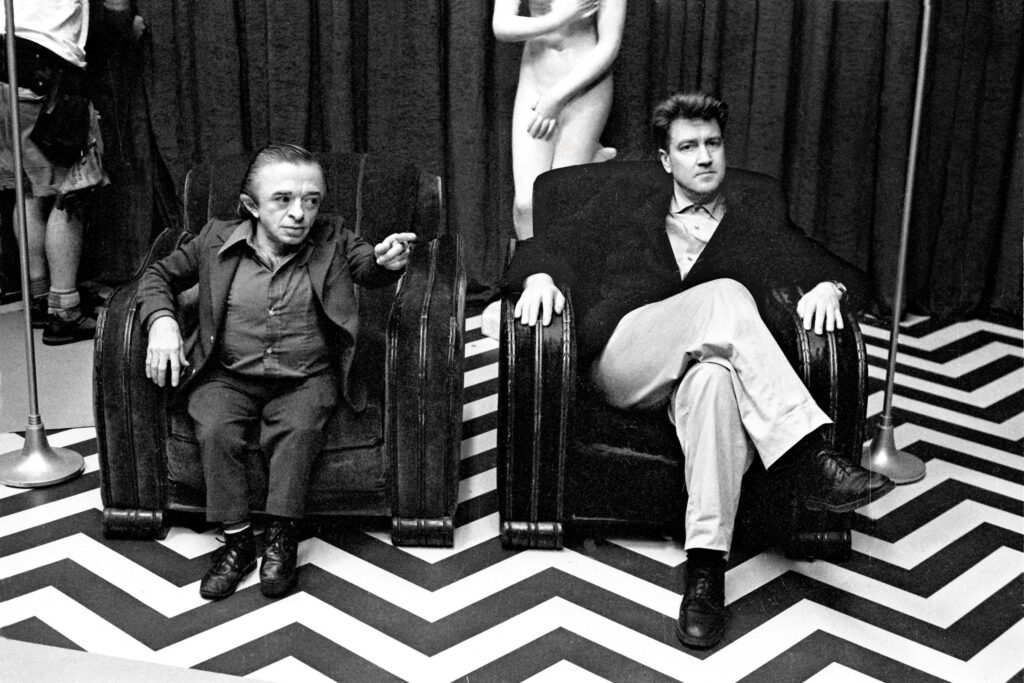

Twin Peaks (1990-1991) revolutionized television by bringing avant-garde filmmaking and surrealist storytelling to prime time. Created by Lynch and journeyman screenwriter Mark Frost, the series kicks off with one of medium’s greatest pilots, in which the discovery of homecoming queen Laura Palmer’s body wrapped in plastic, leads the avuncular FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) to the titular Washington town where nothing is quite what it seems.6Especially the owls.

The show expertly blends genres – soap opera, supernatural horror, police procedural, and comedy – while exploring themes of hidden evil in small-town America. Lynch directed several key episodes, including the pilot and the devastating revelation of Laura’s killer, bringing his distinctive visual style and sound design to television. The show’s dream sequences and Black Lodge scenes, with their red curtains, zigzag floors, and backwards-talking characters, remain some of the most striking images ever broadcast on network television.

While the series famously lost its way for many people in the second season7I don’t think I’m one of them. I’m a true sicko. due to Lynch’s absence, its influence can’t be overstated. Twin Peaks created a template for serialized mystery shows with supernatural elements, creating a tone that echoes through everything from The X-Files to True Detective. More importantly, it demonstrated that television could be a medium for genuine artistic experimentation, helping usher in our current era of prestige TV.

He’d continue the story (in his own way) with Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), a movie that serves as both prequel and dark mirror to the TV series, focusing on Laura Palmer’s final days before her murder. In a move that confounded many fans of the TV show, Lynch strips away the show’s quirky humor to create a devastating portrait of trauma and abuse. Sheryl Lee gives a haunting performance as Laura, transforming the series’ dead homecoming queen into a complex character struggling with generational evil and her own fractured identity.

The film delves deeper into the series’ supernatural elements, particularly the bizarre realm of the Black Lodge and its inhabitants. Lynch’s sound design reaches new heights of discomfort, while his imagery becomes more explicitly nightmarish. Despite the initial reaction being less than favorable, Fire Walk with Me has been reappraised as one of Lynch’s most powerful works, especially in how it gives voice to Laura’s story rather than treating her death merely as a mystery to be solved.

After Twin Peaks, Lynch briefly experimented with two other television series. On the Air, co-created with Frost, was a beautifully crafted and period-accurate slapstick comedy about a live 1950s TV show called The Lester Guy Show. Of course, ABC canceled it after just three episodes.

There was also Hotel Room, an HBO anthology, that presented three stories set in the same New York City hotel room in different decades. Lynch directed two episodes, laden with his recurring themes of identity and violence. It goes without saying that it only ran for three episodes as well. Both programs demonstrate Lynch’s interest in television’s potential for experimentation, even if neither found an audience.

Lost Highway (1997) marked Lynch’s return to feature films, delivering a noir-tinged8I’d love to have gotten the chance to sit down with Lynch to talk about the golden era of film noir. psychological thriller that splits into parallel narratives. The film follows Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), a jazz saxophonist who mysteriously transforms into young mechanic Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty) while on death row. Both men become entangled with women who may be the same person (Patricia Arquette), creating a Möbius strip of identity, jealousy, and murder. The film’s use of The Mystery Man (Robert Blake) and its industrial soundscape created some of Lynch’s most unsettling sequences.

Typical for Lynch’s work, Lost Highway initially divided critics and audiences, with many finding its narrative fractures and dream logic impenetrable. But like Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, the film has gained significant appreciation over time, particularly for its exploration of identity and jealousy through a noir9There’s that word again. lens.

The soundtrack became iconic, mixing Angelo Badalamenti’s brooding score with carefully chosen songs from Nine Inch Nails, David Bowie, Marilyn Manson,10Fuck that guy forever. Rammstein, and The Smashing Pumpkins. Trent Reznor served as music supervisor, creating a dark industrial-rock soundscape that perfectly matched the director’s nightmarish vision. The soundtrack album was a commercial success and helped introduce Lynch’s work to a younger alternative music audience.

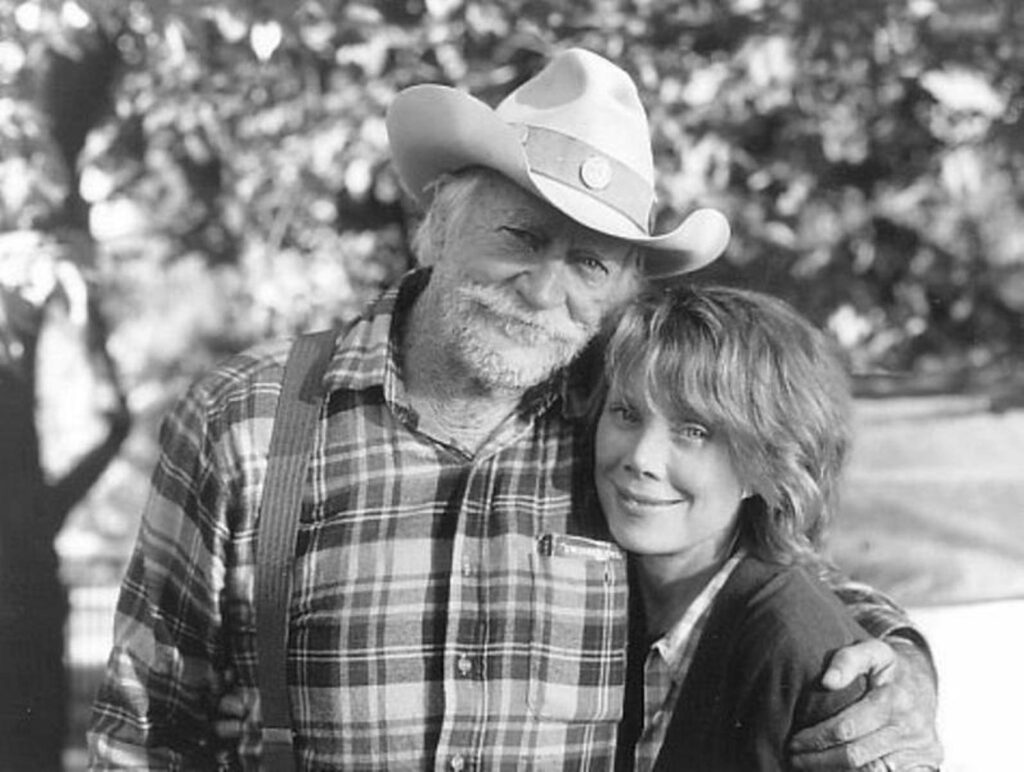

Then suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, was The Straight Story (1999), a G-rated Disney film based on the true story of Alvin Straight, who drove 240 miles across Iowa on a lawn mower to visit his ailing brother. Richard Farnsworth, in his final role while battling terminal cancer, brings remarkable dignity to Alvin, a stubborn old man making one last journey to reconcile with family.

It’s very straightforward and lacks a lot of Lynch’s stylistic touches, but The Straight Story maintains his fascination with American landscapes and the peculiar characters one meets on the road. Shot in sequence along Straight’s actual route, the film unfolds with patient beauty, finding profound meaning in simple encounters and conversations. Freddie Francis’s cinematography captures the heartland’s golden light and rolling fields, while Badalamenti’s score emphasizes the story’s gentle emotional core.

Mulholland Dr. (2001), originally conceived as a TV pilot, emerged as Lynch’s definitive statement on Hollywood dreams and nightmares. The film centers on Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), an aspiring actress who helps an amnesiac woman (Laura Harring) investigate her identity. Then, like Lost Highway, it fractures – revealing a darker reality where Betty is actually Diane, a failed actress consumed by jealousy and despair.

The film’s exploration of Hollywood’s dark side, identity, and desire earned Lynch an Oscar nomination for Best Director. It’s also a movie that rewards multiple viewings, with seemingly random elements (like the mysterious blue key and the terrifying figure behind Winkie’s diner) taking on deeper meaning within the film’s emotional architecture.

Shot over several years on consumer-grade digital video,11A format that Lynch had held a fascination with since its debut. Inland Empire (2006) represents Lynch’s most experimental feature film. The film follows actress Nikki Grace (Laura Dern)12An actor whose work over the years so impressed the director that he staged a sit-in to try to get her an Academy Award nomination for this movie. as she takes a role in a cursed film production. From there, the narrative splinters into a kaleidoscope of parallel stories, involving Polish sex workers, sitcom rabbits, and multiple versions of Dern’s character moving through increasingly nightmarish scenarios.

The film’s low-fi digital imagery creates a uniquely unsettling atmosphere, with Lynch using the medium’s limitations to generate new forms of visual anxiety. Close-ups of Dern’s face become distorted landscapes of emotion and identity. The three-hour runtime allows Lynch to fully embrace dream logic, with scenes flowing into each other without conventional narrative connections.

It’s polarizing even by Lynch’s standards, but Inland Empire represents his purest exploration of identity dissolution, the dark side of Hollywood, and the way trauma fractures both memory and reality. It would be his last feature film until Twin Peaks: The Return.13But not his last work; he remained active, continuing to make short films, commercials, music videos, and even a Duran Duran concert video that I have yet to see.

Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) emerged as one of the most ambitious and radical works of television ever created. Lynch, directing all 18 parts and co-writing with Mark Frost, used the shift to pay cable14It aired on Showtime, creating a collective viewing experience that could only be matched by the original series and maybe, just maybe, The Sopranos. to transform the original series’ format into something far more experimental and challenging. The show follows multiple threads, including FBI Agent Dale Cooper’s 25-year imprisonment in the Black Lodge and his doppelganger’s crimes in the real world, but conventional storytelling takes a back seat to pure cinematic experience.15In fact, Lynch described it as an 18-plus-hour film.

The series reaches its apex in Part 8, a mind-bending hour that travels from a nuclear test in 1945 to the birth of evil itself, rendered in some of the most striking monochrome imagery ever broadcast. Lynch embraced digital technology to create new forms of uncanny imagery while still maintaining his handcrafted approach to sound design and atmosphere.

The show expands far beyond the town of Twin Peaks, creating a cosmic mythology that encompasses multiple dimensions and timelines. Kyle MacLachlan delivers a tour-de-force performance in three distinct roles, while Lynch himself brings unexpected depth to his returning character, FBI Deputy Director Gordon Cole. The series also serves as a meditation on time and aging, with the original cast 25 years older and some, like the late Catherine Coulson (The Log Lady), filming their scenes while seriously ill.

The finale, rather than offering resolution, opens up new questions about the nature of reality and identity, ending with Laura Palmer’s primal scream echoing through multiple universes. It’s a fitting culmination of Lynch’s career-long exploration of dreams, trauma, and the mysteries that lie just beyond our understanding.

As we moved into the social media era, Lynch became a personality that was bigger than his work for many. The painter, musician, YouTube weather guy, transcendental meditation advocate, and even coffee brand owner16One of the only Lynch-related products I can say is out-and-out-terrible. was a touchpoint, a common thread that brought together Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z through an uncommon kind of art.

To parallel with his online popularity, Lynch’s late-career acting appearances revealed him as a surprisingly nuanced character actor. In Lucky (2017), he delivers a touching performance as Howard, a man distraught over his missing tortoise – bringing both humor and genuine pathos to what could have been a purely eccentric role. The fact that he was working with his friend Harry Dean Stanton in one of Stanton’s final films makes his performance especially poignant.

Most popular, though, was his appearance in Steven Spielberg’s quasi-autobiopic The Fabelmans (2022). Spielberg cast Lynch in a memorable cameo as pioneering director John Ford. Lynch captures Ford’s gruff demeanor and no-nonsense approach to filmmaking, delivering the famous horizon composition lesson to young Sammy with perfect crusty authority.

As a creator in multiple mediums, Lynch’s work consistently explored the darkness lurking beneath seemingly perfect surfaces, the enigmatic nature of identity, and the power of dreams. His influence extends far beyond cinema – you can see traces of his aesthetic in everything from modern television to video games to music videos. While it’s frequently misused, the appellation “Lynchian” came to mean a creation’s unique ability to make the familiar strange and the strange familiar.

Throughout his career, Lynch remained steadfastly true to his artistic vision, refusing to explain his work’s meaning and encouraging viewers to find their own interpretations. As he famously said, “The thing about ideas is that they come to you, and you fall in love with them and… you’ve got to stay true to those ideas.”

In an era of increasingly formulaic entertainment, Lynch reminded us that cinema and TV both could (and perhaps should) be dangerous, mysterious, and genuinely surprising. His legacy isn’t just in the films he made, but in the doors he opened for other artists to explore the dark, strange and surreal in their own work.17On a purely personal note, his work has continued to bring my wife and I closer together from the day we met. We even have matching tattoos featuring the phrase “Fix your hearts or die.”

The world is a little less weird today, and that’s not a good thing.

Leave a Reply