This was written as the introduction for the Mesilla Valley Film Society’s screening of Underworld U.S.A. in June, 2024.

1961’s Underworld U.S.A.was written and directed during a rough time for Sam Fuller: he was in the middle of a divorce; his mother had just died; his passion project, The Big Red One, had fallen through despite having John Wayne on board, and his previous picture The Crimson Kimono had underperformed at the box office.

The first was understandable; he’d fully admit in later interviews that he was a difficult man to live with. The second was inevitable; death comes for us all. It was the one-two punch of The Big Red One not getting in front of cameras and Columbia’s mishandling of The Crimson Kimono 1Their advertising department had gone for cheap shocks, choosing to play up the taboo nature of the romance between Victoria Shaw’s all-American stripper and a Japanese-American detective, played by James Shigeta in a way that Fuller felt betrayed the materia. that left him feeling truly adrift. In retrospect, it’s a bit of a surprise that Fuller took on another Columbia project so quickly, but maybe he saw the crime picture as offering him a liferaft, a return to familiar material that had helped make his name in his time at Fox.

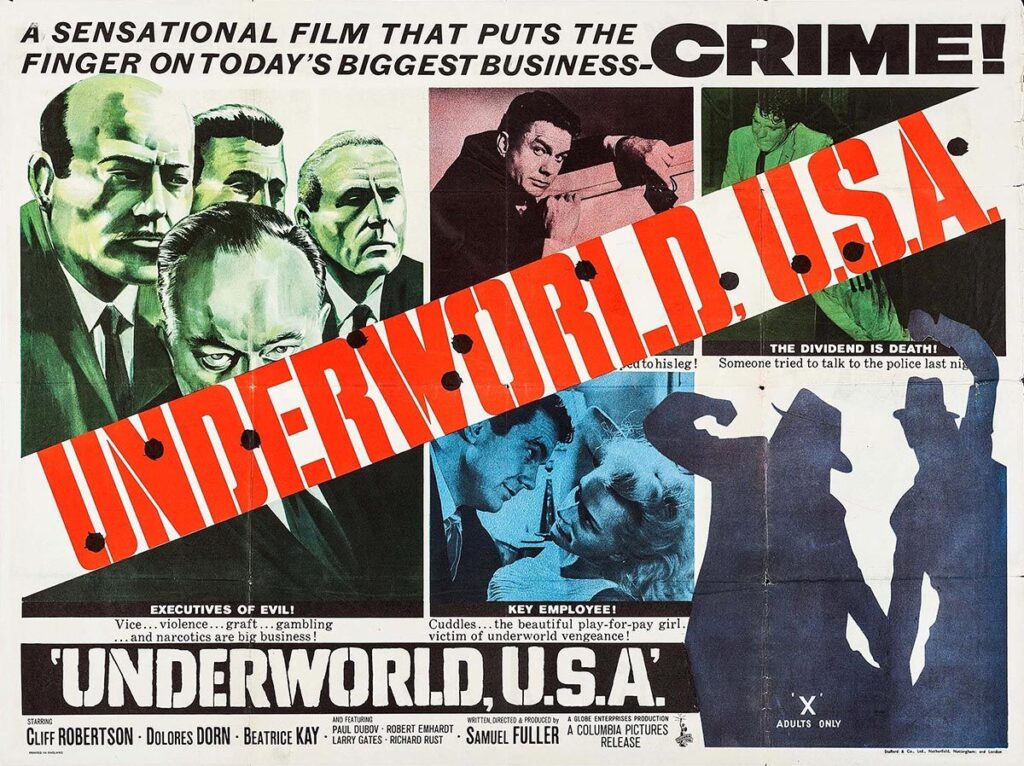

Based on a series of Saturday Evening Post articles written by Joseph Dineen that had gotten a proper book release in 1956,2And previously optioned by Humphrey Bogart’s Santana Productions prior to his death. Underworld U.S.A. promised to offer the frankest depiction of the world of organized crime yet from a major studio. It had everything a guy like Fuller loved – prostitution, drugs, violence – and he had even bragged to Variety that it was going to be a no-holds-barred look at the entire mess.

That didn’t quite come to happen. Without the protection of a producer like Daryl Zanuck, Fuller found himself butting heads with both the Production Code Authority and the studio over the screenplay. He wanted to open the picture with a monologue by a prostitute who would try to sell the audience on the idea of not just legalization of her chosen field, but the unionization of sex workers as well. As she went into the details of how much her and her peers contributed to the American economy, the camera would pull back to reveal a map of the United States made up of near-naked women and the title of the picture.

You won’t be seeing that tonight. Sorry.

With all of his struggles to write a screenplay that met the desires of the studio while also scripting a movie he would be proud to helm, it took Fuller over a year to get Underworld U.S.A. ready to shoot. He would later say that the movie was compromised but he was still proud of what he got on screen, a riff on The Count of Monte Cristo where Cliff Robertson’s Tolly takes on the organized crime cartel responsible for his father’s death by any means necessary.

That cartel, by the way, is presented in a way quite unlike any previous filmmaker’s approach to the mob. They wear suits. They pay taxes. They work out of offices and boardrooms. They’re not embarrassed by what they do; they just don’t want to make a show of it.3You’d see this same approach appear in John Boorman’s Parker adaptation, 1967’s Point Blank. That makes Tolly’s anarchic, brutal approach to revenge even more effective for the audience.

Fuller may not have been able to get all 18 “sick, disturbing” murders of his initial screenplay on screen because of the PCA. Sure, the director had to tone down organized crime’s connections to police departments across the country because the studio didn’t want to make the public feel insecure about the cops. Despite ample evidence of the truth of the matter, he wasn’t allowed to go into length about just how much money drugs made, nor how many people made a healthy living off them.

But what Fuller did get on screen, it sings. Robertson’s a force of nature, an unstoppable engine of vengeance who is as charismatic as he is repulsive. When it does go into the workings of the mob, the movie goes further than any movie made by Hollywood would manage for at least another decade.

Sam Fuller would make one more movie for the studios (the war pic Merrill’s Marauders) before going his own way with the one-two punch of Shock Corridor and The Naked Kiss and while he may never have made another crime picture on the scale of Underworld U.S.A. again, what he left the audience with is a triumph of working within the studio system, limits and all.

Leave a Reply